Every so often there’s an adrenaline-rush day for the small craft operators in Bahia Tenacatita, as illustrated in this photo taken by Aimee aboard sv Terrapin. Is the “Featured Image” missing above? Visit this post on GalivantsTravels.com.

West Coast accessories?

Most important lesson so far

Don’t get in front of the breaking wave if at all possible, and especially, don’t get sideways to it. Also, the kill switch, which turns the engine off when the clip is pulled: you want its lanyard on your wrist and the switch in good working order. You could dump the dinghy, douse your outboard in salt water, lose whatever you were carrying, etc. Better not to chop up the remains while you’re at it. Who needs that kind of excitement?

Two families with four young children between them, headed ashore in kayaks last year, and got in too far to turn back. They got dumped on the way in, and as conditions worsened with the tide, they decided to stay at the hotel down at the end of the beach, rather than take on the waves they photographed above.

It’s an interesting story, since the hotel isn’t set up for that kind of guest, and they weren’t set up to be there. But it reinforces one of our rules, which is: when you go ashore, no matter where you think you are going, always take shoes and always take money.

Feel the surge!

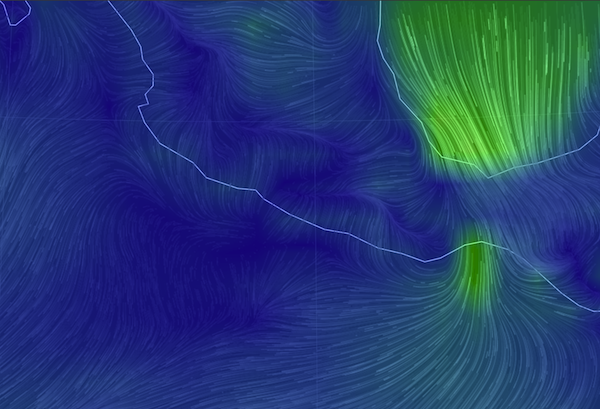

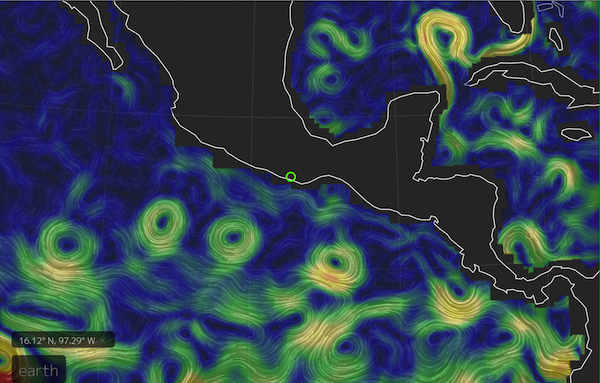

The other day we had some surge-y conditions, and I don’t think anyone went ashore. According to surf sites like magicseaweed.com, there was a 2.3 meter swell train from the northwest, trending down some violent-looking weather systems battering northern California. And there was a 1.4 meter southwesterly swell, can’t say what is generating that without looking south of the equator. These were long period swells, up and down every 15 or 20 seconds. Listening, particularly in the wee hours, you can hear the boom of surf on the other side of the bay.

We are well-anchored, but it is disconcerting to watch our neighbors zooming forward, as if they’re getting underway, and to know that we’re doing the same ourselves. We just can’t feel the conveyor belt we’re riding.

Feel the Roll too

But we can certainly feel the side-to-side rolling that comes when the swell and the wind are perpendicular. There’s an accessory for that too. The flopper-stopper is rigged to hang from a pole stuck out the side of the boat. In the water is something that resists being lifted, but sinks readily, like a weighted platform, bucket, basket/check valve, or a big flat hinge. Even if it doesn’t stop the roll completely, it breaks the harmonic cycle. That’s one accessory we haven’t yet acquired.

And no one is going ashore today, at least not in their dinghies. Surfing in would be one problem, getting back out would be another kind, and maybe more difficult.

Launch techniques

We’re learning that the wheels aren’t always the answer to getting out either. The problem is that they leave the bow of the dinghy down, easy for the waves to break into while you’re trying to get into the dinghy, get the engine started, get the passenger aboard, stay steered straight out, etc.

As for ourselves, well, we sometimes come home wet, and glad of a dry bag for storing things. It does help to decide early who is calling the shots, or you’ll both get doused in the space between go, go, go and wait, wait, wait!

Footnote about the panga

*from Wikipedia, I learned this about the ubiquitous panga.

- The original panga design was developed by Yamaha as part of a World Bank project circa 1970.

- Key features of the panga design are a high bow, narrow waterline beam, and a flotation bulge along the gunwale, or top edge of the hull. The high bow provides buoyancy for retrieving heavy nets, and minimizes spray coming over the bow. The narrow beam allows the hull to be propelled by a modest-sized outboard motor. The flotation bulge along the gunwale provides increased stability at high angles of roll.

- The original Yamaha panga design had a length of 22 feet (6.7 m), and a waterline beam of approximately 5 feet 6 inches (1.7 m).

- Pangas are usually between 19 and 28 feet (5.8 and 8.5 m) in length, with capacities ranging from 1 to 5 short tons (0.89 to 4.46 long tons; 0.91 to 4.54 t) and powered by outboard motors of between 45 and 200 hp (34 and 149 kW). Their planing hulls are capable of speeds in excess of 35 knots (40 mph; 65 km/h)