Isabela, one of the newer islands of the Galapagos group far off the coast of Ecuador, was particularly intriguing to me, perhaps because of its remoteness, volcanoes and small population. From the sailing point of view, we liked its anchorage, because there were a few islets and some sheltering reef between us and the open ocean, which is not always the case in the anchorages yachts are allowed to visit. Not that these were always sufficient protection against swell and quirky currents, but they did offer some psychological comfort and a perch within binocular range for wildlife viewing.

Like other Galapagos islands we visited, Isabela has volcanoes rising from a coastal plain. In Isabela’s case, there are half a dozen volcanoes that have melded to form a seahorse-shaped island 80 miles long. Isabela’s volcanoes are young and they’re active, so there are big areas of absolutely no vegetation. Talk about empty! Yet there are farms and fincas in the heights of the volcano closest to town, Sierra Negra. There is a mellow little town, Puerto Villamil, of maybe two or three thousand people, and tourists too, including a good number of students on ‘summer abroad’ class trips.

It’s a great place for touring on a beach-cruiser style bicycle. We unstowed our folding Dahon ‘bicicletas’ and went as far as our little legs could pedal us, which by this sign board is about two inches along the south coast west from Puerto Villamil and its harbor about midway across. The big cone in the middle of the southern part of the island is Sierra Negra, which we visit later, Negra/black perhaps because it’s active and the lava fresh and black and plentiful. And Alcedo is right in the middle, where you’d cinch your belt. The volcanoes up top, Darwin and Wolf, are visited, if at all, by people on the tour excursion boats, not by yachts.

A couple yachts passed through on their way to the Marquesas while we were there, but Isabela is best for R&R, not for provisioning. The food there is mostly imported, and there is very little water, or fuel (unless the barge is in). Unlike the whaling-ship days, no one is loading tortoises for later consumption, although there are wildlife conservation issues aplenty.

Here is the Australian schooner Windjammer, bound for Easter Island and Chile. You can read about their trip here: http://www.sailblogs.com/member/schoonerwindjammer/

Isabela has its attractions

I’m not a surfer, or much of a beach-goer, but if I were, I could walk to a beach right in town with lots of waves, and lots of white sand, and enough reef to be interesting. It’s not always this rough.

Humedales or ‘wetlands’

In town, and along the south coast to the west are a series of, I’ll call them water features, since they seem like various iterations on the theme of lava tunnels filled with sea water, or brackish lagoons near the coast. This network has lots of interesting birds and different types of vegetation, including several mangrove forests. The trails take you in areas you’d otherwise miss, and of course there’s lots more to see and wonder about when you can get close and watch from a strategically located platform or bench.

I never knew that a flamingo’s wings had a different color underneath. Or that they ate by shoveling their lower beak through the mud.

Wall of Tears

Further out of town but still within bicycle distance is a perverse monument to man’s inhumanity to man in the form of a rock wall 100 meters long and 8 meters tall, known as the Wall of Tears. There was a penal colony here from 1945-1959 and the prisoners were made to build this wall, tear it down and build it again, over and over. ‘Weak men die and strong men cry’ said the reader board. It was July, a cooler season, when we were there, baking in a bright blue noonday sun. It must have been misery, even for ‘criminals’ who maybe made other people miserable, or maybe were just poor, but the pointlessness of the task is what particularly distressed me.

The penal colony was built upon the remains of a US radar station from WWII. Even before that the area had been overrun with introduced species, leading to this sign:

The pig, the donkey, the cow, cat and rat, you could shoot them all, maybe on the same day, once you gained entry to the zone! All non-native invaders, all highly disruptive to the local flora and fauna.

Tortoise hatchery

It seems each island we visited has a tortoise hatchery. The one on Isabela also served as a refuge for a subspecies rescued from a lava flow that they couldn’t move away from fast enough. Not sure about the breeding and hatching part, but keeping a corral of tortoises is as easy as building a stone wall. The movement towards more ‘natural’ habitat for enclosed animals hasn’t gone far for these tortoises, but it doesn’t have far to go either!

I’ve been reading recently that the intelligence of reptiles has been underrated; might be true! I keep thinking I’m seeing a spark of curiosity in the eyes of the tortoises that peer at us peering at them. Or maybe they just think we’re bringing leaves. The difference between tortoises and turtles, by the way, is that while they are both reptiles in the family Testudines, tortoises are land-based, and turtles are water-based, with flatter, more streamlined carapaces. Swimming in the high-domed capacious carapace of a Galapagos tortoise would be like a Victorian-era woman bathing in hoop and bustle.

Here’s the first and only tortoise we saw in the wild, big as a hassock maybe, and most likely a graduate of the Isabela hatchery. I got close and s/he scrambled away, which they can’t do at the crianza.

Sierra Negra

We got on the open-sided, wooden-cabin truck-bed ‘bus’ with a trample of tourists for our excursion to view the freshly-lava-spread caldera of the Sierra Negra volcano. It’s surprising how cool and moist the air becomes ascending 1124 meters (3700 feet), but the cool does burn off as the day wears on. Horseback-riding tours are an option, popular with folks from the Galapagos excursion boats; I’m not sure who was more miserable, some of the panicked non-equestrian tourists, or the cranky horses. The horses have been doing it so long they’ve got parts of the trail washboarded.

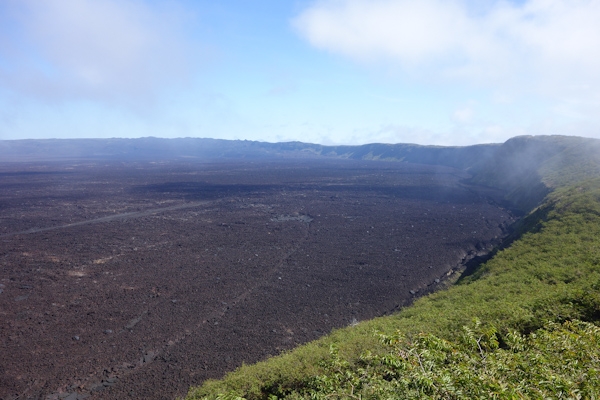

Here’s the Sierra Negra caldera we came to look at, arriving just as the clouds lifted, as promised by the guides.

Way in the back you might be able to see the source of the most recent lava flow. I only pretended that I could. The straight lines that look like paths or roads in the caldera are not, they’re just ‘formations’. It’s a big caldera, 9 km across maybe, and not very deep compared to others, but the most interesting thing about it is that almost all the vegetation growing down the sides (there’s lots more on the southern walls) and around the top is Guava (Psidium guajava), one of my favorite fruits. Here it’s a weed, which as we know, is just a plant growing in the wrong place, or worse, as here, a terrible invasive. Guava is displacing all the local flora and upsetting what was the natural balance. I’m so used to associating leafy and green with healthy that the idea of this almost lush spread of guavas being toxic came as a shock to me.

According to galapagospark.org: Guava, which is characterized by a high rate of germination and regeneration, spreads rapidly on the fertile plains and areas of Scalesia spp. This weed is slowly covering the plains of the Sierra Negra and Cerro Azul Volcanoes.

But once guava was kept behind the fence at the mountaintop plantation. The scalesia, one of several species being crowded out, is in the aster family, with flowers like daisies, but 12 species are shrubs, and 3 are trees, quite unusual, except in the Galapagos.

Then we marched ourselves over to a smaller caldera for a closer look at more volcanic features. The bright spot is a sulphur fumarole or something like it, not sun through cloud.

And I like how so much of volcano vocabulary, like the types of lava, pahoehoe and aa (aa is the clinker-like one that it hurts to walk on, ah-ah), are Hawaiian in origin.

Here are some closer views:

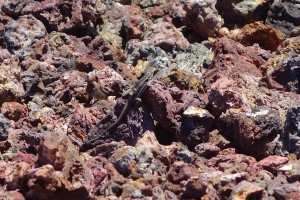

You could call this landscape lunar, but I wouldn’t – there’s ocean visible just beyond, and some plants gaining a toehold, a couple insects and a lizard. And no trash – our guide, the excellent Edgar Daniel, was fierce on this point, reminding us to hold on to every bit of our lunch and its packaging. But this lava field is the tabula rasa, barely formed and almost pristine, of the next Galapagos, which probably won’t be much like the former one. I’d like to make a special trip back to see how it turns out.

Romantic?

I’ve been puzzling over my curiosity about places like Isabela, and I’ve decided that it’s the romance of the place, or better said, my idea or vision of the place, that intrigues me. The dictionary informs me that romantic may indeed be defined as ‘an idealized view of reality’. I plead guilty! In that case, nothing says it better than this 1984 photo by Frans Lanting of tortoises in the crater of the Alcedo volcano.

He describes his photo so:

In a geologic sense, the islands are young, yet they appear ancient. The largest animals native to this archipelago are giant tortoises, which can live for more than a century. These are the creatures that provided Darwin with the flash of imagination that led to his theory of evolution. ..Immutable as the tortoises seem, they were utterly vulnerable to the buccaneers and whalers who took them by the thousands in the last two centuries. But one population eluded them. Inside the Alcedo volcano on Isabela Island, an earlier era lingers. This caldera is sealed off from the outside world by steep lava slopes that rise to 3,860 feet on the equator. It was not until 1965 that an Ecuadorian biologist found a way down inside and discovered a world where giant tortoises roamed in primordial abundance. This group had presumably never seen humans. ..They hadn’t seen many more when I entered the time capsule of the caldera. For one memorable week, I lived among the tortoises of Alcedo. Photography one morning was one of those precious experiences where I could be part of a scene rather than a distant observer. The tortoises were resting in a pond as soft mist mingled with sulfur steam from nearby fumaroles and dust from an erupting volcano to the west, and I was able to create an image that evokes the era when reptiles dominated life on land."..- Frans Lanting.

In case the watermark doesn’t show up, the featured image at the top of this post should also be credited to Frans Lanting, and is available at

franslanting.photoshelter.com

I’m not sure if these tortoises survived the spread of feral goats to the area, but I have read that the tortoise population outside the crater is beginning to recover following a massive, as in perhaps 80,000 goats, eradication program conducted with land hunters, shooters from New Zealand in helicopters, sterile female “Judas Goats’, a full and costly array of attempted extinction.

Here’s a bit about it from http://www.galapagos.org/conservation/project-isabela/

The giant tortoises on Alcedo Volcano provided the catalyst for Project Isabela. In the 1970s the feral goats present on southern Isabela finally crossed the hostile terrain of the Perry Isthmus and arrived at the lower southern slopes of Alcedo Volcano. It would take another 10 to 15 years for the goat population to explode causing massive ecosystem degradation. The destruction was most evident on the southern rim of Alcedo, a gathering place for giant tortoises during the cool, dry, garúa season. The dense forests on the rim created shade and the critical drip pools where tortoises congregated. The thick garúa mists drifting up the outer slopes of the volcano became trapped in the many epiphytes living in the forest and then dripped to the pools below. But the goats arrived like bulldozers, destroying the forest and thus the tortoise shade and water supply. Other native and endemic species, including birds, insects, and plants, were also negatively impacted by the destructive goats, whose population continued to expand to the more northern volcanoes, Darwin and Wolf. Their arrival at each new portion of Isabela resulted in pristine forests and shrubby vegetation being transformed into barren grasslands and in massive erosion of the steep volcanic slopes.

Now, how romantic is that? And then, reading comments on stories about the goat eradication program, you’ll learn that many commenters feel that the “Darwin hand” should be played out to its logical conclusion. Don’t kill the poor innocent creatures, just let whatever is going to happen, happen, they say. Sounds more like a tragedy to me. But I’m not a goat (so far as I know), just a curious romantic, easily intrigued.