My parents vacationed in Acapulco in the 1950s. Their stories of the pink hotel where each room had its own swimming pool fascinated me, as did the photos they brought home of men diving off a cliff into a tiny pool of surf. These were the famous Cliff Divers of Acapulco, los clavadistas, as they’re known locally. So it was hard to sail past without stopping.

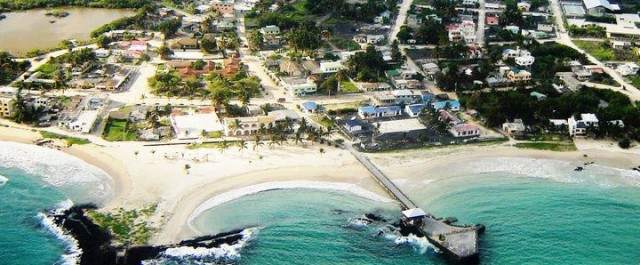

Acapulco is also famous for its beach – has been since before its days as a Jet Set destination in the 1950s. Not many cities can boast such an attractive setting on a large bay, six kilometers across, rimmed with sand, lapped by tropical waters and framed by rising ranks of jagged hills.

Fast forward to the 21st century. And slow down for a stop in early April of 2014.

The older original part of town has a market, square, cathedral, all the usual accoutrements. The tourist area however is a shadow of its former self, aside from the fort San Diego, now a nice museum. The action has moved along the beachfront towards the big hotels. If there were any action, I should say.

It’s astonishing just how empty of tourists these big buildings are, as measured by lights at night.

The cab drivers and people we chat up on the street agree it’s pretty quiet lately. But they insist that every room will be filled during the Easter vacations, Semana Santa.

Economic wheels are still turning and there’s plenty of local traffic and activity on the roads. I am charmed by all the VW bugs being used as taxis. They were manufactured in Mexico until 2003, and I’ll bet it would be a great place to get parts if you had an VW to refurbish.

Part of the problem has been an increase in violent crime in recent years, but there is general agreement (our main sources are taxi drivers and bartenders) that things are better now than they were five or six years ago. There may still be murders, but they’re ‘back there’ said one taxista, gesturing toward the interior, ‘poor people and gangs. Let them fight and kill themselves there.’ He told us there was a period where he was afraid to work at night, but, ‘it’s all better now.’ It takes a long time for a town’s reputation to recover though.

Galivant’s crew might have liked to rub elbows at the Acapulco Club de Yates, where the sailing events for the 1968 Summer Olympics were hosted, and the gardens have been well-tended ever since, not to mention the pool. I got to walk through, looking for a marine store. We would have looked a ridiculous in our weathered little sailboat next to some of those glossy big motor yachts at the dock, and felt even worse counting out a couple hundred dollars, plus tax, plus electric, for a night’s dockage. So we went across the bay, anchored near the navy base, and took the dinghy ashore, to be looked after by Jorge the jet-ski renter for the price of a couple beers each day.

And how empty the beach! Several miles out of the harbor we were noticing discolored water – clearly a ‘red tide’ event happening at the moment. They should actually be called algal blooms, since the toxic phytoplankton are not always red, and have nothing to do with the tide. But they’re not healthy on your skin or in your mollusks, in addition to being visually unappealing.

Where we left the dinghy on the beach, (near a bar called Pancho’s) there were a few one-umbrella food and drink stands and something of a local community, with dogs, who looked after things, including us. A near-toothless older (I hope) gent explained to me that those little jellyfish and plants would die and rot and fertilize the eggs of things that were growing in the sand and that “a different intelligence was at work than this one”, waving his hand dismissively toward the high-rises. I thought he summed up the algal bloom versus development scenario pretty nicely. Also ‘they’ say that when the bloom is over, the water is super-clear and clean. Maybe the Semana Santa tourists will be blessed.

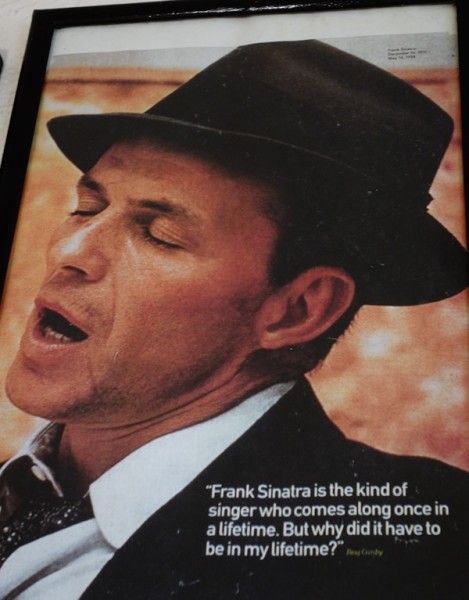

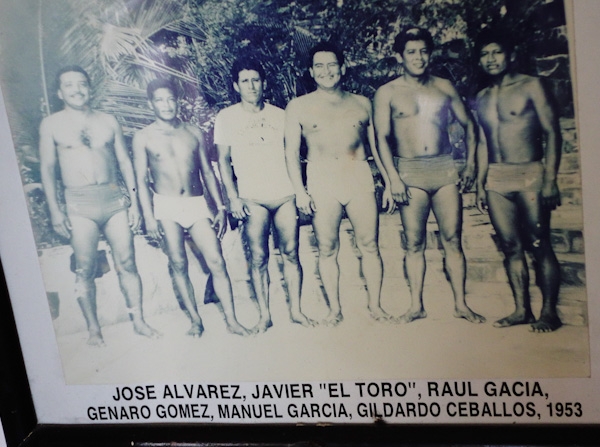

Then we did our part for the local economy by attending the clavadistas, and eating in the restaurant while doing so, mainly so we could sit in the shade. The divers have been on several ‘extreme sport’ shows, the Hotel Mirador featured in an Elvis Presley movie, and the celebrities of the Jet Set and more modern eras have made appearances throughout the years since the first dives in 1937. Or at least PR people sent photos. Aside from Roy Rogers and Trigger both signing the wall, here’s the one I liked best.

And now, ladies and gentlemen, the divers.

They ‘commute’ to the job site by jumping into the water from the observation terrace, swimming across, and climbing up the rock face to the shrine. Some, not all, pay obeisance to the Virgen.

The top height, by the shrine, is 125 feet, and the average water depth is only 12 feet deep, so they wait for an incoming surge of water. And as you can see, the ‘out’ from the cliff is at least as important as the ‘down’.

Believe it or not, no diver has died, although there have been injuries mainly related to miscalculated approaches to the water. And we noticed that a diver always waited at the bottom, moving in several times to clear away bits of debris from the landing zone. Luckily the algal bloom wasn’t in this area, although a patch was visible offshore. We heard that there is a 12-year old girl starting to dive, but didn’t see her.

When they finish, the divers sell t-shirts and mingle with the visitors. I wish I had been better prepared financially when I found them waiting for us as we emerged from the restaurant.

There is one show during the day, and four in the evening, with flaming torches. I’m really glad I went, but I’ll probably wake up in the night feeling vertiginous!

We walked down the hill to the old center, the Zocalo, where we found a nice church and a plaza under shady trees with a dozen shoe-shine booths spaced beneath them.

We probably should have taken a walk through the market with a very pleasant older man named Tony, but our next mission was the museum at the fort of San Diego.

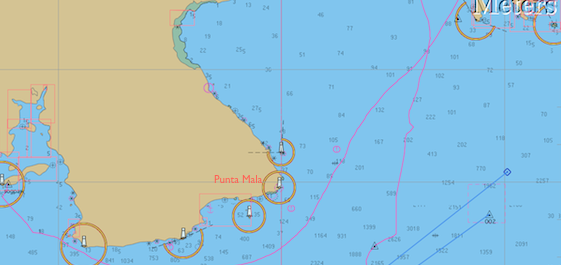

It’s a well-done museum, (extra points for reader boards in English). Turns out Acapulco Bay has been a shelter and a destination ever since the Spanish first came here. Not such a surprise, really, since there are precious few good harbors along this coast, but I was unaware of the scope of Spain’s trade with the Philippines, in terms of ships, cargo and the hundreds of years it continued.

It took these ships nearly 100 days (departing for Manila in March or April) to go west, and 180 to return (departing July or August), for those that made it past the bad weather and pirate attacks.

Winding up our day, we walked back a ways along the beach-side road as it slowly turned into a seaside restaurant and shopping zone. A bonus was seeing a US chain that sold a brand of shampoo I like. Such are the smaller pleasures of travel.

I hope the friendly folks of Acapulco get lots of tourists for Semana Santa, and beyond, and I hope the visitors have as entertaining a time as we had there.