February and March are the height of the season for whales in Baja California. They are here, like us snowbirds, for the warmer water, but also (possibly unlike many snowbirds) for birthing and breeding.

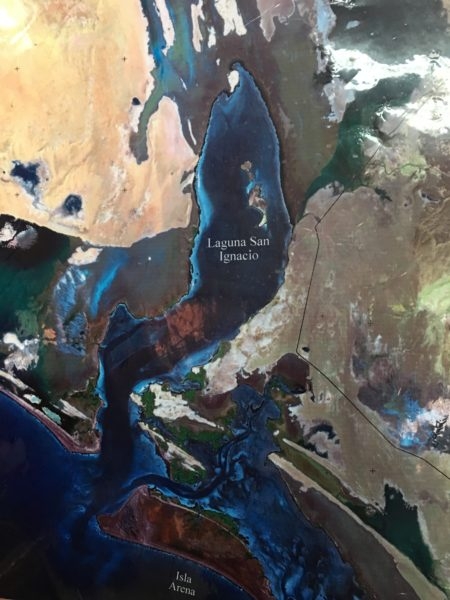

We see whales as we sail inside the Sea of Cortez. But the concentration is far greater in the lagoons of the Pacific coast of the Baja, such as Lopez Mateos, Magdalena Bay, Laguna Ojo de Liebre and Laguna San Ignacio. Grey whales in particular migrate to this area. So, taking advantage of a safe place to leave Galivant, on a mooring inside Puerto Escondido, we rented a car and drove off towards San Ignacio.

Getting There

It’s more than the 3:07-hour trip to San Ignacio that the Google Map algorithm thinks it is, but it is a pleasant drive through Loreto, Mulege, and Santa Rosalia and across the mountains on a decent road with coastal and hilly scenery. Know too that there is more road between the town and the lagoon; the last fifth (12 km) of that road is pretty good for a dirt washboard, but more comfortable at slower speeds.

In San Ignacio itself you’ll find another of the Jesuit missions from the 1700s that run down the spine of the Baja. It is a pleasant small agricultural oasis town. Wikipedia reports a population of 677 souls in 2010.

What a nice downtown square they have, big and shady.

We had thought to sleep in town, but we also wanted to go out on the boat early in the morning, so we’d have time for the drive home.

When we heard how much more road there was between town and the lagoon, sleeping at the Kuyima camp started to sound like a good idea.

Luckily for us, a tent was available on the beach. We had an early breakfast with the staff and got going before ‘the big group’ that arrived. Sometimes no plan is a good plan.

In the miles of beach, there are several other camps, more or less like this, well spaced, and there is a small, cobbled-together-looking area not built for tourists, with a church and cemetery, a place to buy beer and a small airfield. A mile or so inland, closer to the mountains, I was surprised to see lights at night, and I think that must be where the locals live – camp staff, fishing families, ranchers, far from the water’s edge. We see hurricanes tracking up this coast pretty regularly, and nothing on the waterfront would survive the winds, the seas, or even the rains. Everything along the beach has an impermanent appearance.

And now, the whales

The gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus), also known as the grey whale, gray back whale, Pacific gray whale, or California gray whale is a baleen whale that migrates between feeding grounds like the Bering Straits and breeding grounds such as Baja California yearly. It reaches a length of 14.9 meters (49 ft), a weight of 36 tonnes (40 short tons), and lives between 55 and 70 years.[5] The common name of the whale comes from the gray patches and white mottling on its dark skin….The gray whale is the sole living species in the genus Eschrichtius. This mammal descended from filter-feeding whales that appeared at the beginning of the Oligocene, over 30 million years ago. So says Wikipedia.

These whales, in this place and in the other lagoons along the Pacific coast, were slaughtered in big numbers. Between 1846 and 1874 over 8000 whales were killed in these lagoons by American whalers, not to mention the calves left wounded or orphaned in the lagoons.

The whales fought back, attacking whaleboats, maiming and killing whalers. The whalers called them ‘devil fish’. The fishery was abandoned when the whale numbers declined precipitously in less than a generation.

However, present population is thought to be around 20,000, possibly the ‘optimum sustainable population in the present ocean ecosystem’, according to NOAA and Wikipedia. On the day of our visit in mid-February it was announced that about 168 whales had been counted in the lagoon on the most recent daily flyover. We could see them spouting all around.

Given the bloody history it surprised me to see that the grey whales acted quite friendly. Why would they want to come anywhere near us? And it doesn’t seem right for us to mess with any wild animal.

But I can’t deny that when the lancha came out to the designated area, the whales arrived straight away, looked us over, and came right alongside without hesitation, in fact, with alacrity. The launch drivers did nothing special to attract them. The whales seemed to welcome the touches they got, floated alongside and under the boat for minutes at a time, kept turning and coming back, and perhaps got as much from the experience as the boat passengers did. In fact, if the touching stopped, the whales went to another boat. And so it went for over an hour.

There are government-mandated rules of engagement, such as: no more than 16 boats in the entire designated watching area, no more boats than 2 per whale, no boats between two whales, no speeding, etc. According to one National Geographic article (link at bottom of page), the fishermen take their roles as protectors of the whale very seriously – ‘the well being of these whales is critical to the well being of the fishing community.’ And so it seemed.

The baby whales are a solid slate gray, clean and fresh looking. We did see a youngster with its mother at another boat and have read that mothers have been seen nudging the juniors towards the boat.

The older whales have characteristic grey-white blotchy patterns said to be scars left by parasites which drop off in its cold feeding grounds. Our driver told us that the barnacles fell off when the animal was in Arctic waters. True? I’ve also read that barnacles are sometimes scraped off one side during baleen feeding close to the bottom, depending on whether the whale is right-mouthed, or left-mouthed. True? There sure are a lot of well-attached mature-looking barnacles.

Thinking of my own skin, the largest organ of my body, and how nice a good scratch can feel, I can believe that the whales might enjoy being rubbed and fondled by us, if that’s not too anthropomorphic a thought. I wonder if those barnacles are as annoying as I imagine them to be.

Another point of interest I read somewhere is that these friendly whales are only this friendly in the lagoon. During their migrations, it’s all business. Also, the skin of whales, dolphins and other maritime mammals, atop their blubber, is thin and sensitive, particularly around the blowhole, genitals, mouth and flippers. They are capable of sensing changes in water pressure and turbulence. Gray or Grey? Both, inconsistently, everywhere!

So, it was a stellar experience – one I’d recommend, now that I can see how it is initiated by the whales.

More information

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/photography/proof/2017/08/gray-whales-baja-mexico/#close

NG has written the blog post I wish I could have written with the photos I wish I could have taken!

Kuyima.com is the whale watching tour operator we used and liked. And they have something to say about grey whales too, here: http://www.kuyima.com/whales/greywhales.html

The Saving of the Gray Whale (People, Politics and Conservation in Baja California) by Serge Dedina- one of several books in the dining area that I skimmed through, wishing I had time to read it all. Same could be said for Lagoon Time: Our Life and Times Among the Whales of Laguna San Ignacio by Steven Swartz. And of course, there’s the internet. These grey whales are very charismatic!