SEE UPDATE REGARDING FEES after paragraph five

|

On either side of the canal it’s easy to recognize boats about

to change sides, because of the dozen or so car tires wrapped in plastic

stacked on the dock or deck. This time it was our turn. |

Yes, it’s official. We transited the Panama Canal, all fifty miles of it, from Atlantic (north) side to Pacific (south) side, this past weekend. Although we spent New Year’s Eve as many people do, not even resolving to stay up late, it’s hard to avoid a new 2013 mindset to go with the new 2013 location. Still, we haven’t formulated any real plans other than casting an eye towards Ecuador and the Galapagos.

A canal transit agent can make all the arrangements for those who care to pay his fee – about $350 for a boat our size. But we were traveling not in the busiest transit season (that would be February, March and April, when the Polynesia-bound boats generally move.) And we had good instructions, from the SSCA Bulletin of June 2011 (thanks Ainia). So we made the arrangements ourselves.

Basically it required two visits to town, the first to the Signal Station to arrange to be measured, and the second to pay the fee, in cash, at a particular bank in a safe area across from the Port Captain’s office. (It takes special wardrobe functions to get all those bills out of one’s underwear in a public place!) Then there were a couple phone calls to the Scheduler’s Office. For us, it went like clockwork.

The measurer and his tape measure came to the marina, filled out the forms, made sure we could provide a toilet and fresh water (preferably bottled!) to the advisor, and that the boat could go fast enough to make the trip. The fee, for boats whose total measure (including the part of the anchor that sticks out the front, and the steering gear, or davits etc at the other end) is less than 50 feet, is $1875, up $375 from this time last year. An as yet undetermined amount of that was our ‘buffer’ fee and will be refunded, I hope. The main advantage of the agent, as I see it, is that he covers the buffer fee for his clients, and provides lines and fenders.

UPDATE: about a month from when we paid, we had an email from the Canal Authority indicating that our US bank would not accept the funds being wire-transferred to them: “the beneficiary account has restrictions” and upon further investigation “Panama is on a restricted list”(aimed at money laundering?). So we arranged to pick up a check for $866 at the Panama Canal Authority, meaning that our transit would cost basically $1000 (credit for the wire transfer, plus tire rental $2 to receive $1 to discharge, per tire. We also rented four 125′ 7/8″ lines for $60. We could have used our own lines, long enough, but they are only 3/4” and we didn’t want to chance being dinged by a faceless bureaucrat. In retrospect, we should have used our own lines.

Here’s a great note I received from a friend about his two canal transits:

After reading your comments on your canal transit, I couldn’t help but think of the fees we had to pay for the two transits we made. The fee for the one in 1971 in our 30 ft Seawind Ketch was a bank-breaking $18 dollars. In those days we had to pay based on the same formula for tankers, freighters etc . It was based on a boat’s cargo holding capacity. The second transit in 1998, this time in our Valiant 40 Tamure, the fee was $118.

So, here follows a photo journey thru the Panama Canal. And, if you’re curious about the story of the present canal, which is in fact full of cultural, political and social as well as historical interest, a book I’d recommend is Panama Fever, by Matthew Parker. Also, loads of factoids at http://panamacanalmuseum.org/index.php/history/interesting_facts

|

Kim and Steve and their son Tim came along as line-handlers.

It’s good practice before coming through on your own boat. |

PHOTO BRAZILIAN REEFER KIM STEVE

We locked through the ‘uphill’ three locks lashed to the port side of another sailboat a wee bit larger than Galivant, trying to stay in the center of the lock. Ahead of us was a ship, the Brazilian Reefer, behind us a tugboat tied to the wall. Between the turbulence as the lock fills, salt water mixing with fresher water, the ship’s propellors and the tugboat’s smoky exhaust, plus a little inattention aboard the boat to which we were yoked, and activity in the neighboring lock, the first lock was a little exciting.

PHOTO LINE THROWERS

The men with the monkey’s fists do a very neat little maneuver as they heave their lines towards us (we covered the solar panels with our cockpit cushions, just in case!). We tie their line through the loop on ours (‘You do remember the becket bend, don’t you’, says Doug) and they haul it back, drop it over a bollard and then disappear as the lock fills. They send our line back to us, but walk us, along with the messenger line, to the next lock, and so it goes through the three locks which raise us over 80 feet.

PHOTO OUT LOCK GATE 2

It’s quite an odd feeling to look down at the Caribbean waters ( hard to see but I can assure you they’re there, stepping down in the distance) as the lock gate closes behind you!

PHOTO LOCK AT SUNSET

It was getting pretty dark by the time we finished with the uphill locks and were let loose in Gatun Lake, less than a mile above the dam from where we had stayed in the Rio Chagres. It would be wonderful to spend a couple days in the lake poking around, but that is strictly forbidden, although you could go in a kayak!

|

| Photo by Kim Watford |

We were expected to, and did, spend the night tied to this ship mooring. Luckily the weather was still and there were only five us, to share the two moorings – sometimes there are half a dozen boats all on the same ‘hook’! Can’t anchor because of ‘lots of trees underwater.’ And by no means should we swim, because of crocodiles. In fact, we saw a croc about 8 feet long floating in one of the locks, but he was dead.

Sunday morning 6:30 found us motoring through the lovely mountaintop lakes for our special date at 11:15 at the Pedro Miguel lock. Staff offered up coffee juice bacon eggs potatoes refried beans salsa and raisin toast. The captain drove. And Ricky, our advisor, cheerfully answered every question as we crept along the side of the channel.

Each boat is required to have an ‘advisor’, but these are not ‘pilots’ (the official pilots perhaps see the small boats as not quite worthy of their attention.) Rather, the ‘advisors’ are drawn from the ranks of canal employees such as firemen and security officers, and are required to have a university degree and to speak English. Ricky’s other job is aboard a hydrographic vessel, but he says he likes this one better and has transited the canal about 70 times a year for four or five years now. When the yachts go through tied to each other, there may be a sort of pecking order discussions among the advisors, which can cause confusion. But we liked Ricky and were pleased when he joined us again on the second day.

PHOTO SATELLITE IMAGE (from 2005) OF PANAMA CANAL COURTESY eorc.jaxa.jp

These lakes are the reservoir for the copious quantities of water necessary each time the locks are filled. Some of the islands are built of fill from construction of the canal. The Smithsonian has a nice tropical research facility along here, as the lake coast is undeveloped and likely to stay that way.

With explosives and dredging, the bends and curves of the shipping channel are gradually being straightened and deepened for the arrival of the new generation of super-container ships being made possible by construction of new super-sized locks parallel to the ones we just came through.

PHOTO SHIP UNDER BRIDGE WITH TUGS

The downhill locks seem a little easier to negotiate; they were certainly less turbulent. It’s more interesting to see the lock structure being revealed than to see it covering up. I enjoyed contemplating that all of this was built a hundred years ago of a quality that endures, although not one of the ladders has every single one of its rungs intact.

PHOTO INSIDE DOWNHILL LOCK

This set of locks we shared with a boat-load of tea-drinking bare-chested Brits, and all hundred-odd spectators at the visitor center at Miraflores locks. There’s a web-cam too, but I don’t know anyone who watched it for us, and, thankfully, it wasn’t very exciting.

PHOTO OF YACHT RAFTUP IN LAST LOCK

And then we were out! The skyline of Panama City Panama is getting rather Miami-like; one of the most interesting features is this under-construction BioDiversity museum designed by Frank Gehry. Looks like it will be another couple years before it opens its doors, or should I say, has doors to open! Right now it reminds me of how the sea urchins we see on the reefs often manage to camouflage themselves with little bits of shell.

PHOTO GEHRY BIODIVERSITY MUSEUM CONSTRUCTION SKYLINE

May your own new year also be as pacific and tranquil as you like it, with just the right amount of biodiversity.

A few more photos here: Panama Canal Transit

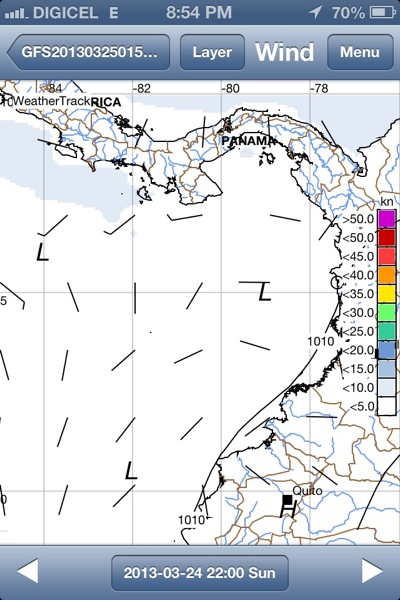

We stepped out into the wider Pacific last week. All the way to Ecuador from the Perlas islands in Panama the wind not only blew moderately but stayed behind us, and the seas did too. The moving sidewalk of current beneath us was pretty much in our favor as well. At times the speed log was showing above nine knots. A person could get spoiled moving as expeditiously as this!

We stepped out into the wider Pacific last week. All the way to Ecuador from the Perlas islands in Panama the wind not only blew moderately but stayed behind us, and the seas did too. The moving sidewalk of current beneath us was pretty much in our favor as well. At times the speed log was showing above nine knots. A person could get spoiled moving as expeditiously as this!

Plus there’s a another fire now, this time at a large landfill, wafting toxic fumes over the city, closing schools and sending folks to the hospital. Friends in the anchorage report that half the skyline is obliterated at times. They have some kind of foam fire stopper coming in from the US and also are using explosives to tame the flames. I read it online! Photo courtesy of newsroompanama.com

Plus there’s a another fire now, this time at a large landfill, wafting toxic fumes over the city, closing schools and sending folks to the hospital. Friends in the anchorage report that half the skyline is obliterated at times. They have some kind of foam fire stopper coming in from the US and also are using explosives to tame the flames. I read it online! Photo courtesy of newsroompanama.com